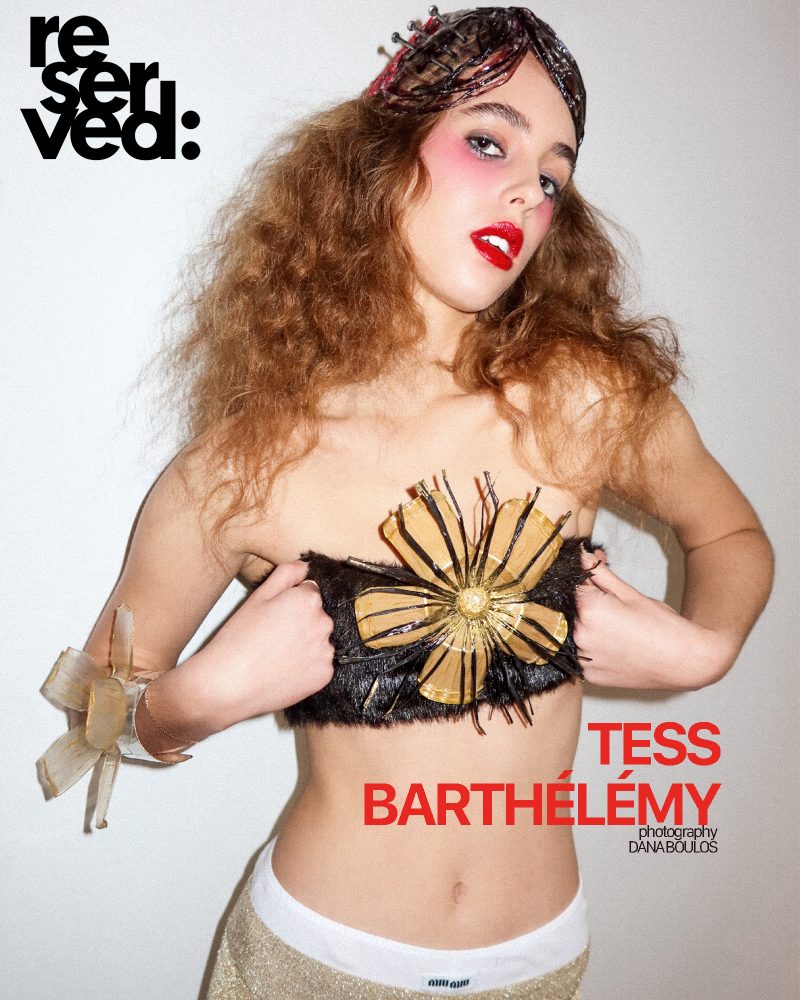

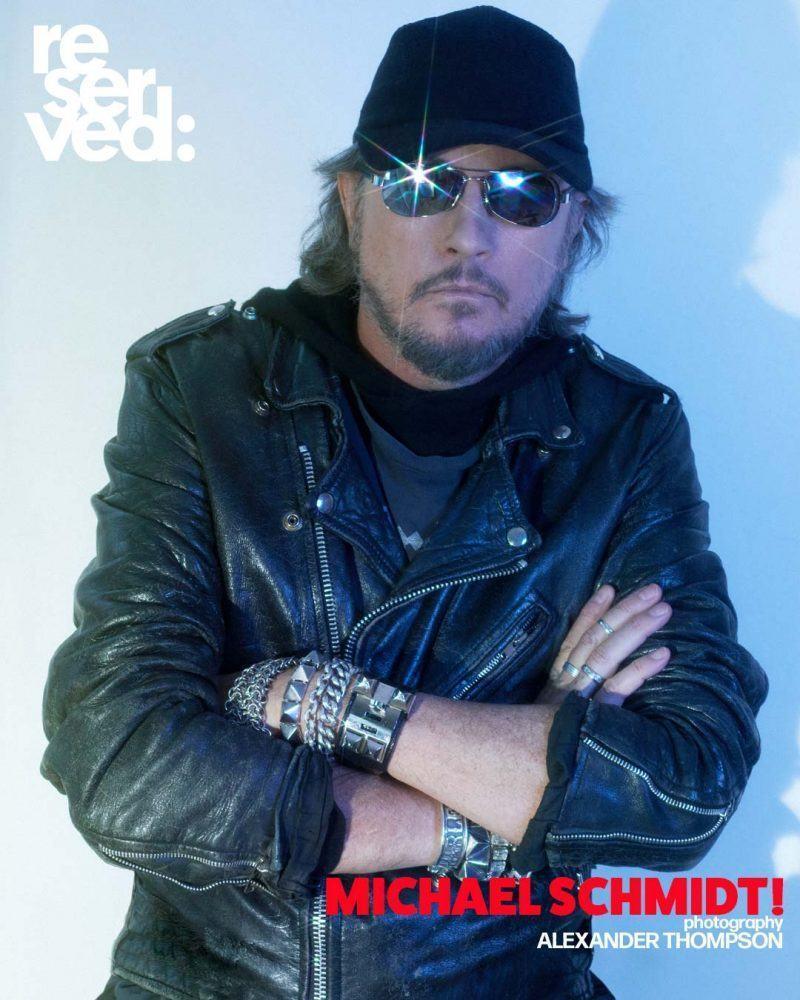

ART & THE DNA OF CREATIVITY

NEIL GRAYSON

by Anthony Haden-Guest

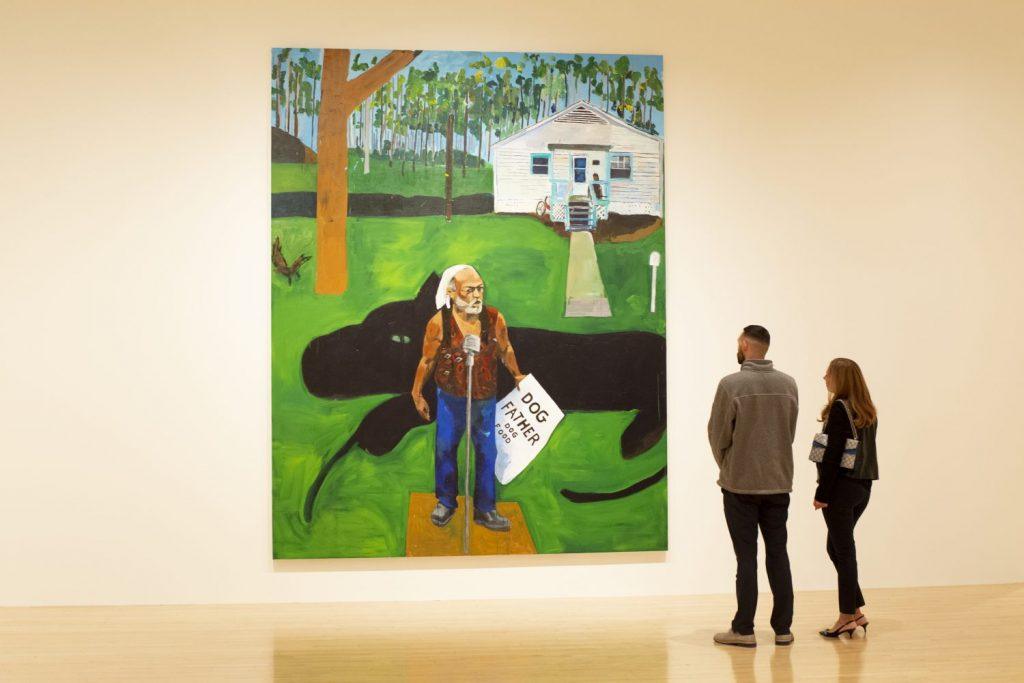

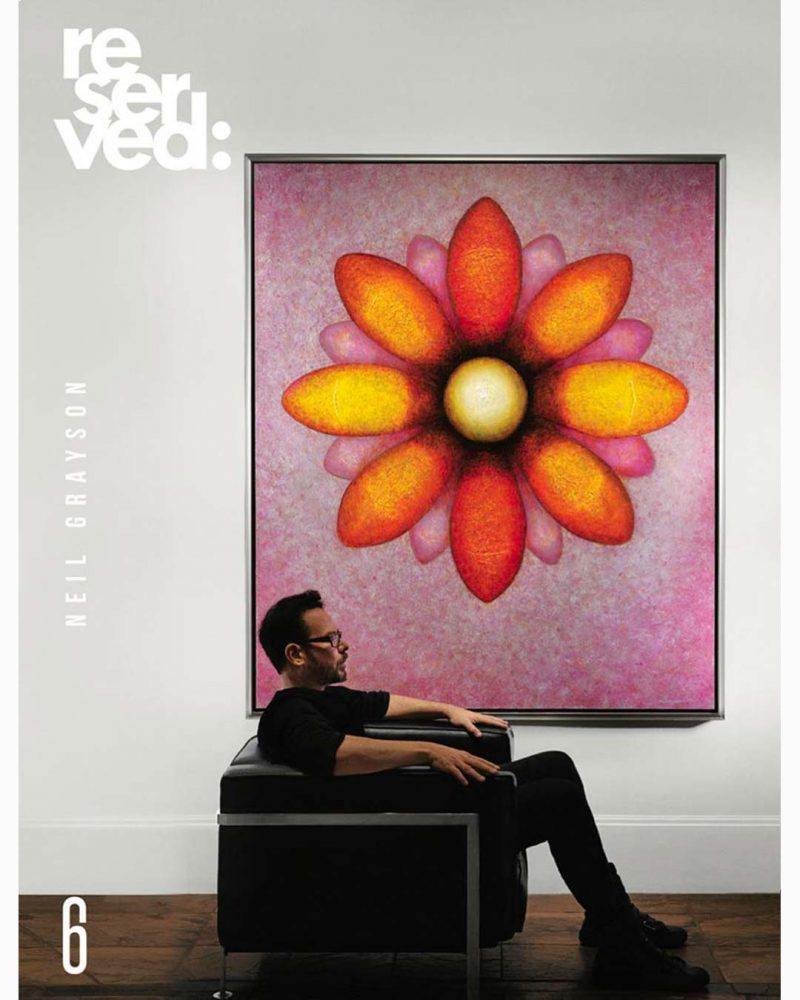

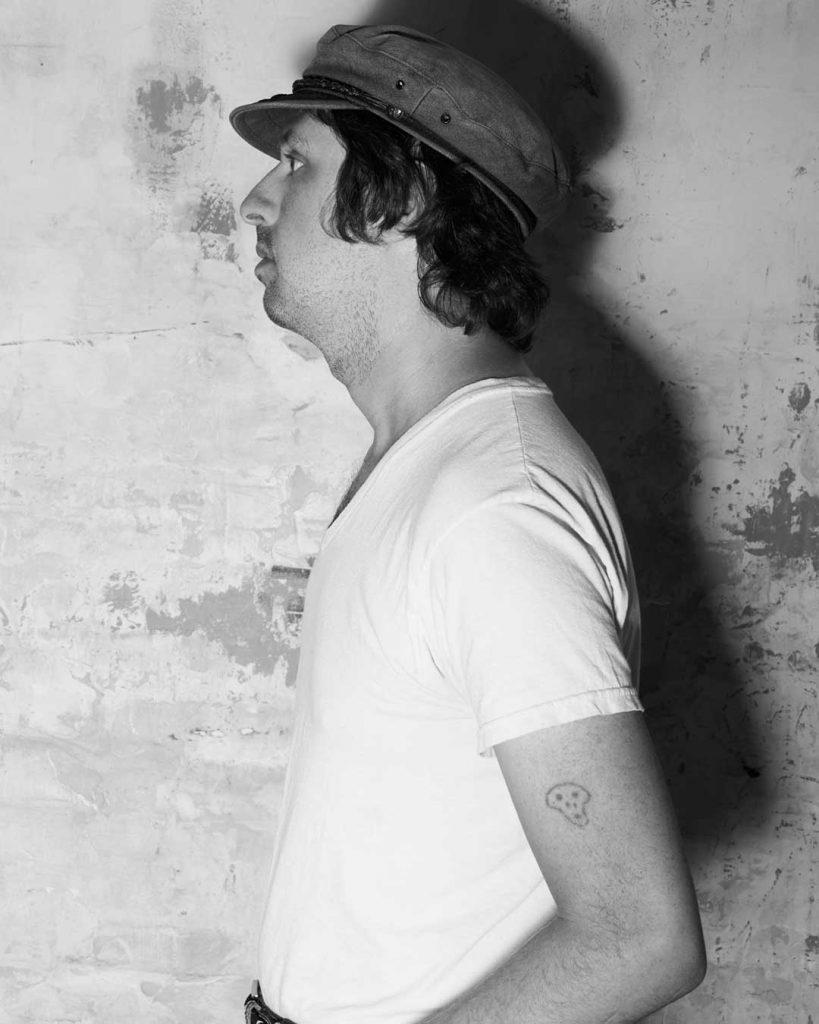

There is an empty frame on a wall in Neil Grayson’s SoHo studio. It’s a handsome frame, hanging alongside his portrait of his father. What he was planning to put in it?

“Nothing,” Grayson said. “That’s Salvador Dali’s last frame. He ordered it before he died.” He had seen it in Heydenryk, the Manhattan framer. “I paid more than I could afford thirty years ago, but I really had to have it. So I just hang it. It’ll stay like that forever. There’s nothing I could put in there that would more make more sense than imagination.”Had to have it! Obsession plays a part in just about any serious artist’s practice, but for Neil Grayson, it’s a driving force. He had been seventeen on his first visit to Heydenryk, seeing to the framing of his copy of his 1660 Rembrandt self-portrait in New York’s Metropolitan Museum. His first major project. “I painted that live in front of all the tourists for six months,” he said, “The Met said it was the best copy they’d ever seen.”

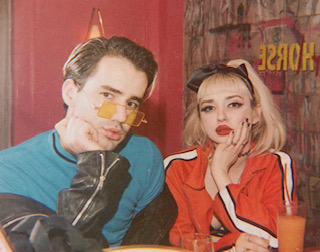

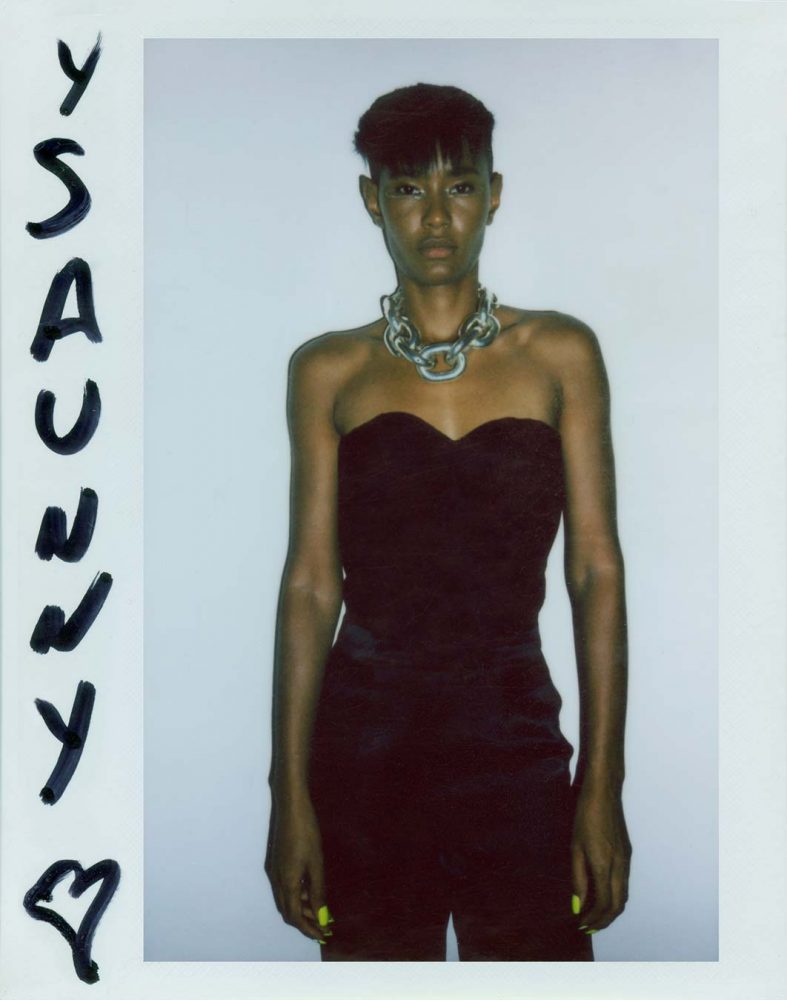

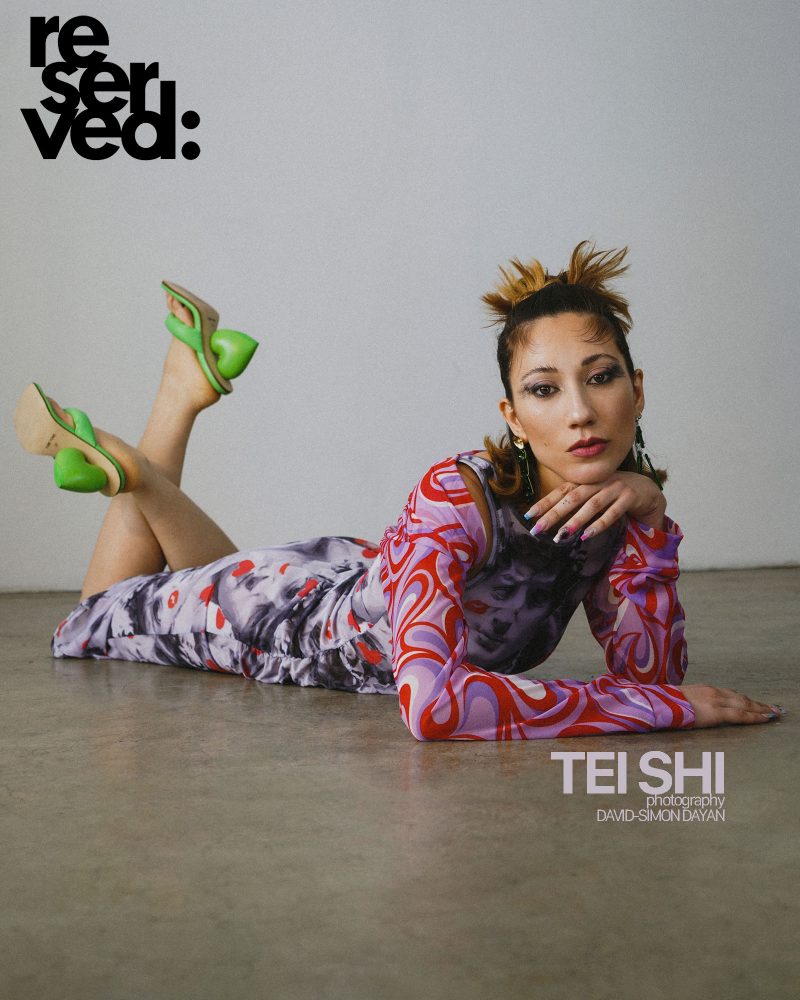

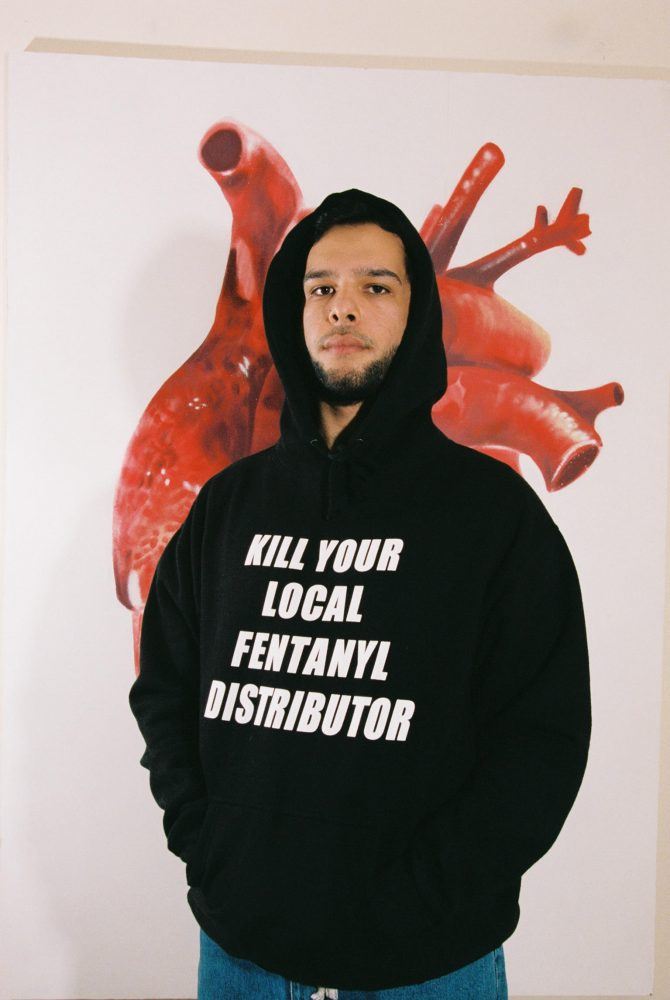

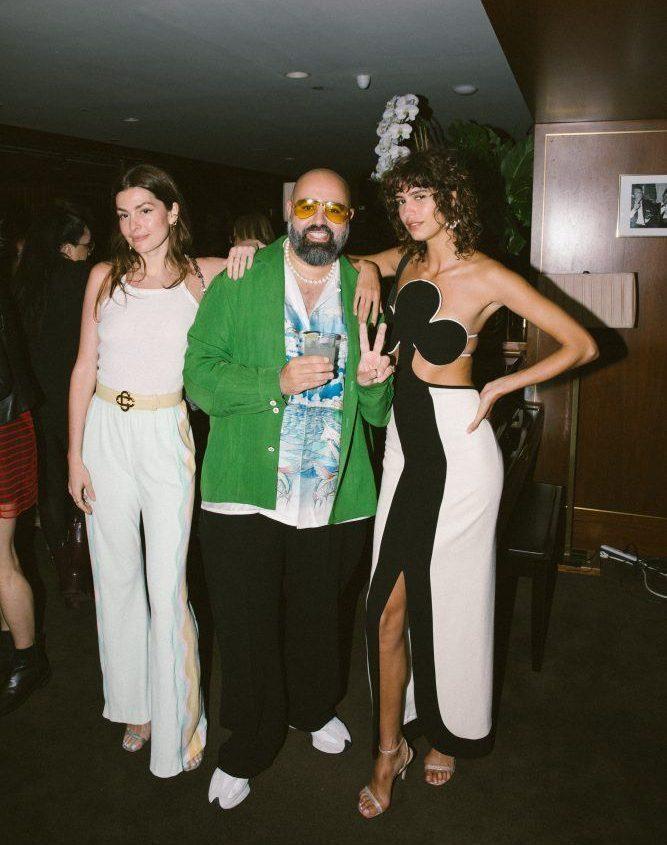

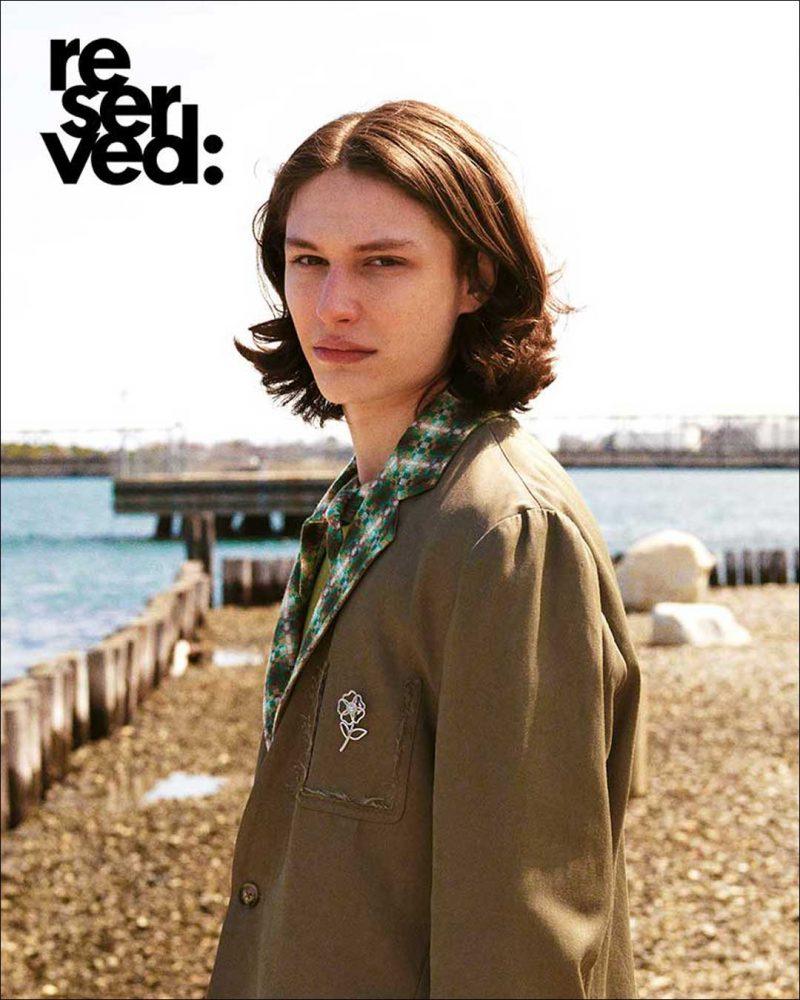

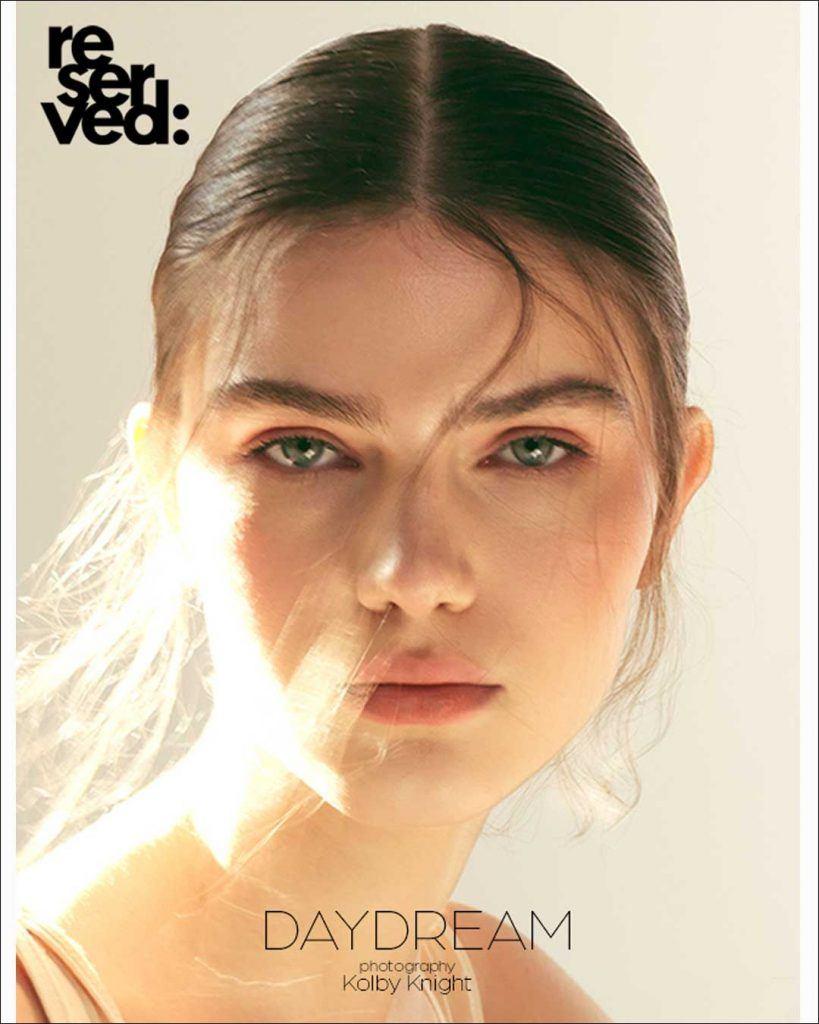

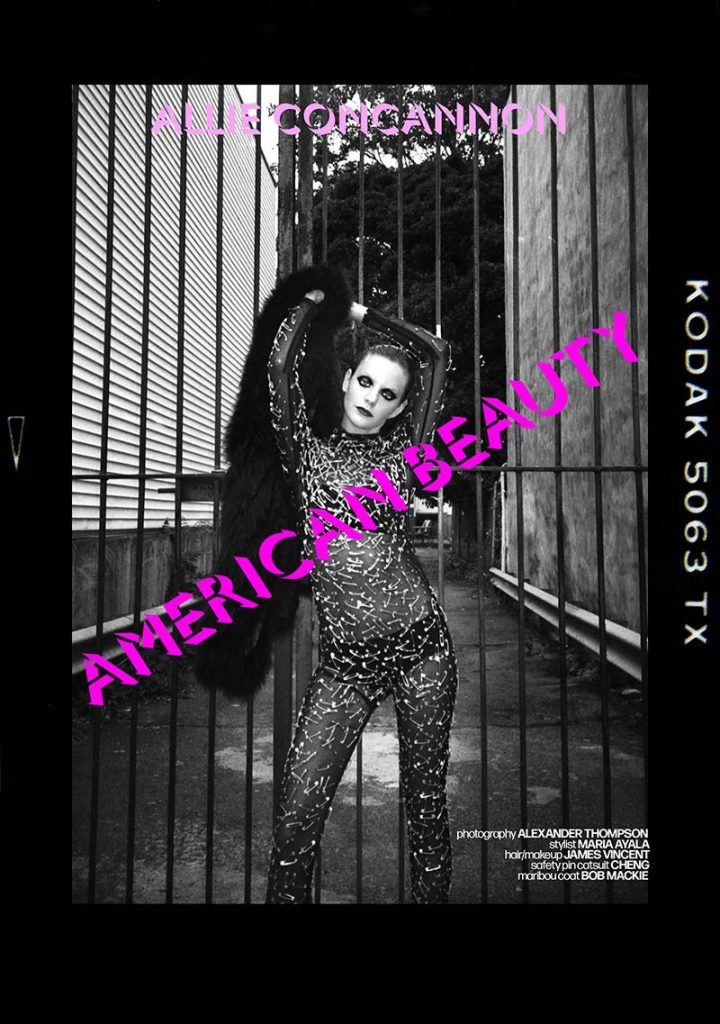

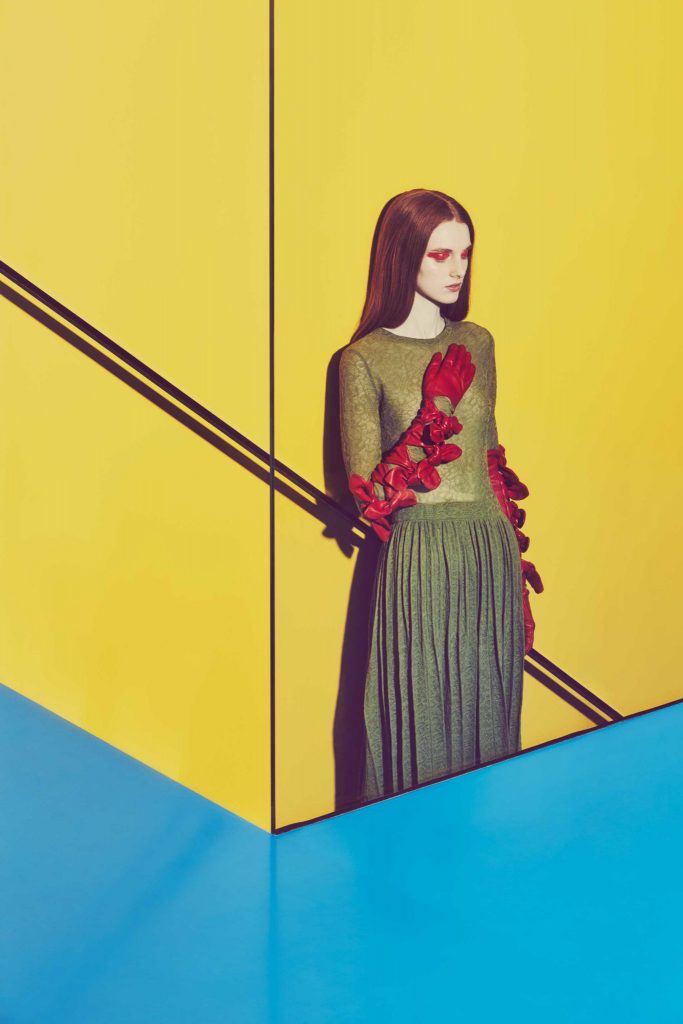

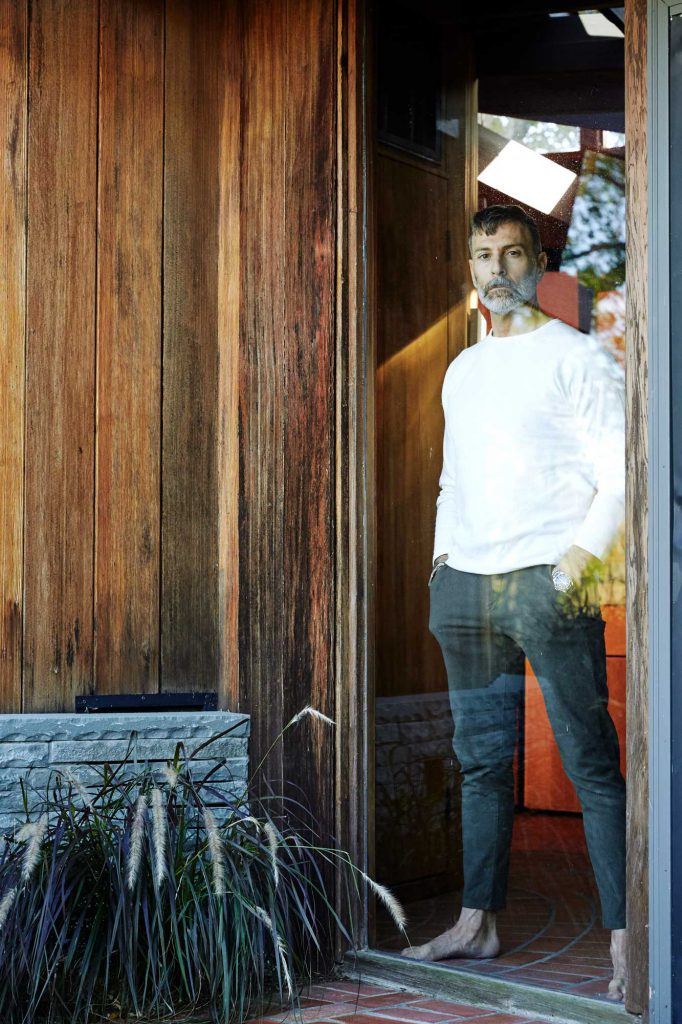

Neil Grayson in his NYC studio with portrait of his father. Herbert L. Grayson, 1987, oil on board, 24 x 20 in.

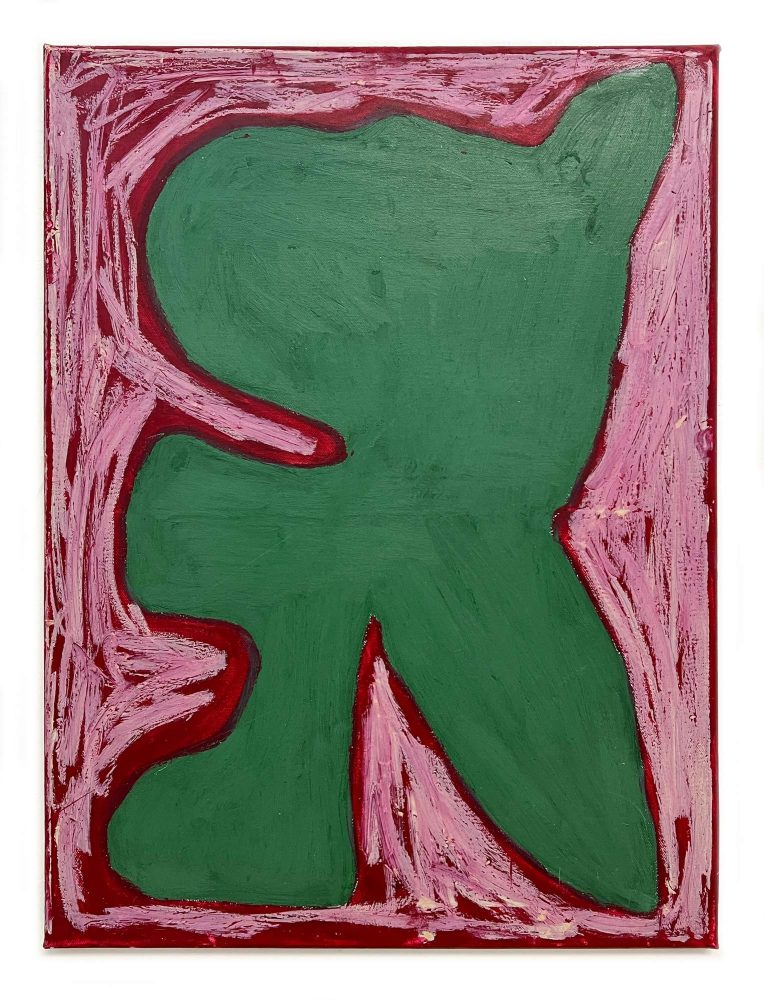

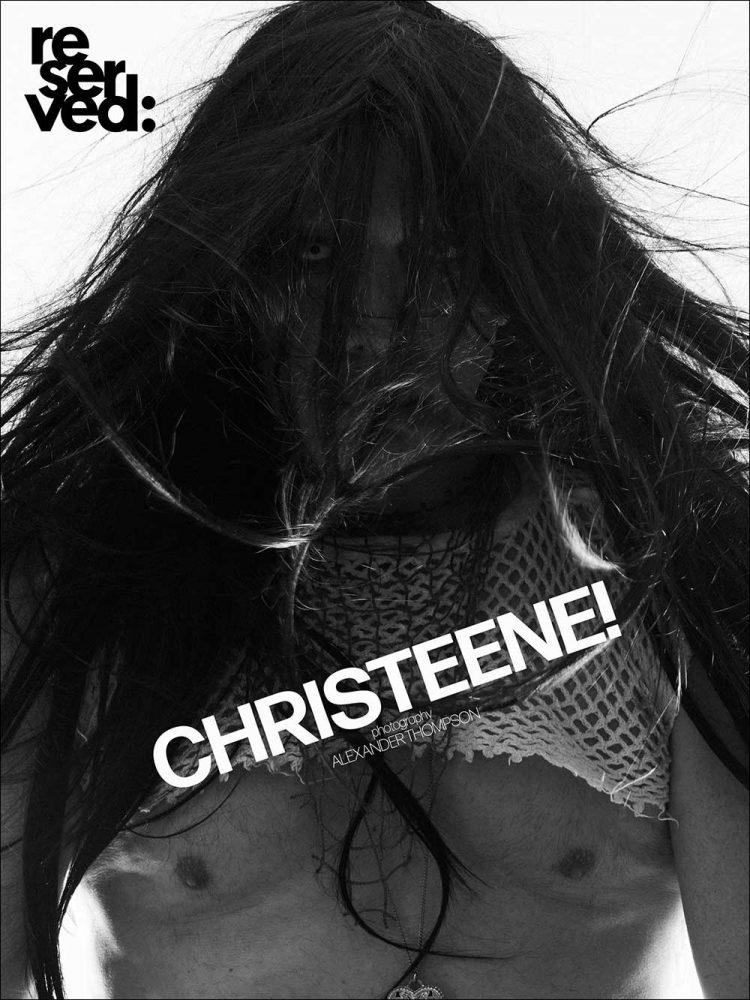

Cerebral Flag. 2012, oil on canvas, 52 x 62 in. University of New Haven, private collection.

The project had deep roots. “I was obsessed with strange things when I was very young. When I was twelve or thirteen I was obsessed with portraiture and poetry. I liked Klimt. I liked Egon Schiele. I liked the rose and blue periods of Picasso.” But mostly he liked the Rembrandt self-portrait. “It wasn’t so much the actual portrait. It was what I describe as the singularity, the glow of light, chiaroscuro. It was how Rembrandt developed that intense focus, the triangulation that brought you into that illuminated sphere. I did everything possible I could do to learn everything about Rembrandt’s portraiture when I was a child. I wanted to master this light in darkness.”

So young Grayson began making regular visits to the Frick and the Met on Fifth Avenue to study classical portraiture techniques. “There’s a technique in classical portraiture that you use very lean, low fat, low-absorption oil paint at the beginning,” he said. “You paint fat over lean to keep the paint from cracking. The lowest oil density paint at the time was chromium oxide green,” which he taught himself to use. The museum visits continued for years. When he was eighteen he painted the portrait of his father hanging next to the Dali frame. So that was a mission accomplished for traditional classical portraiture. Grayson describes his next move as a leap.

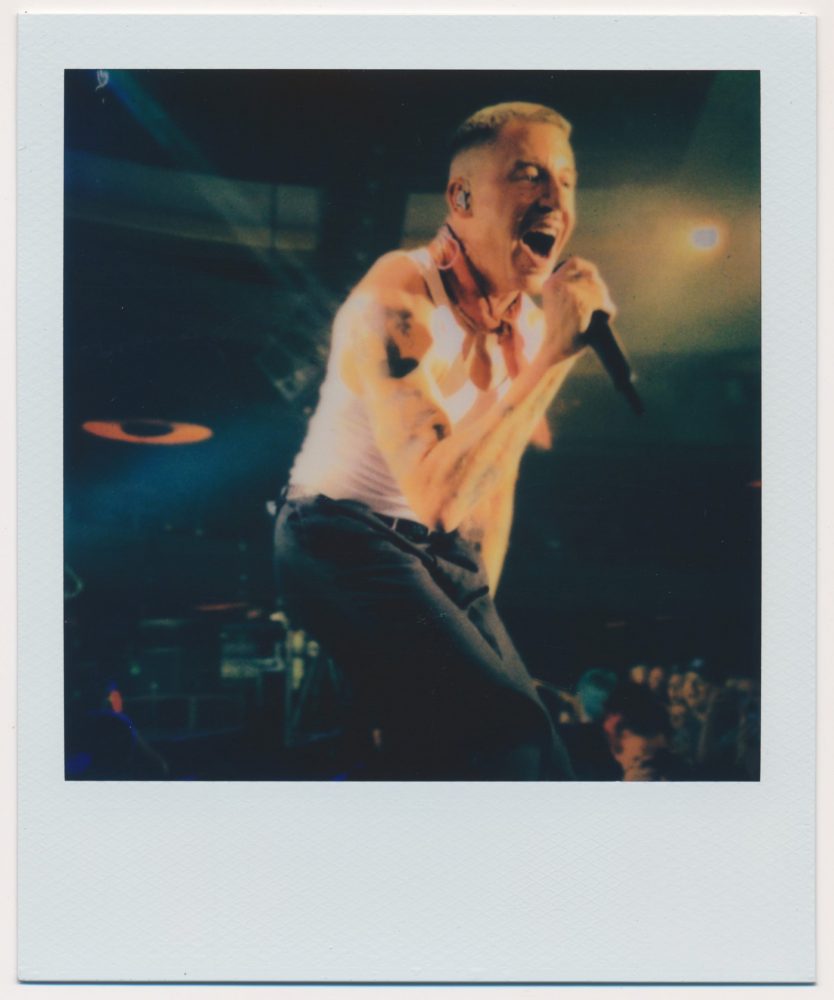

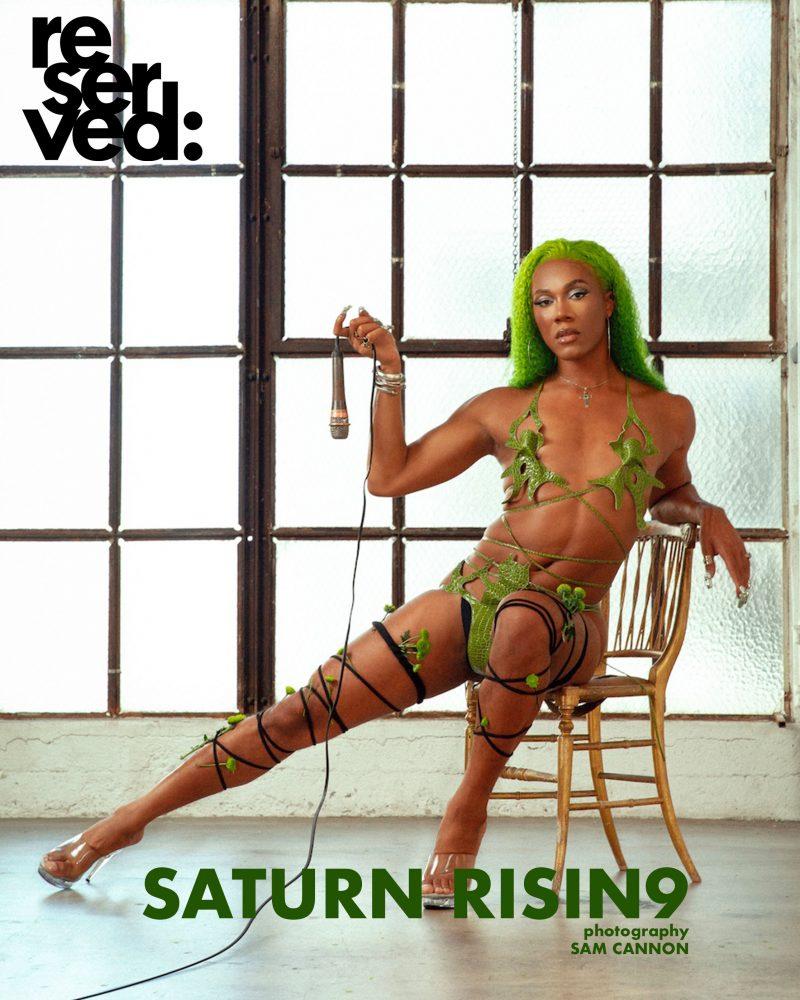

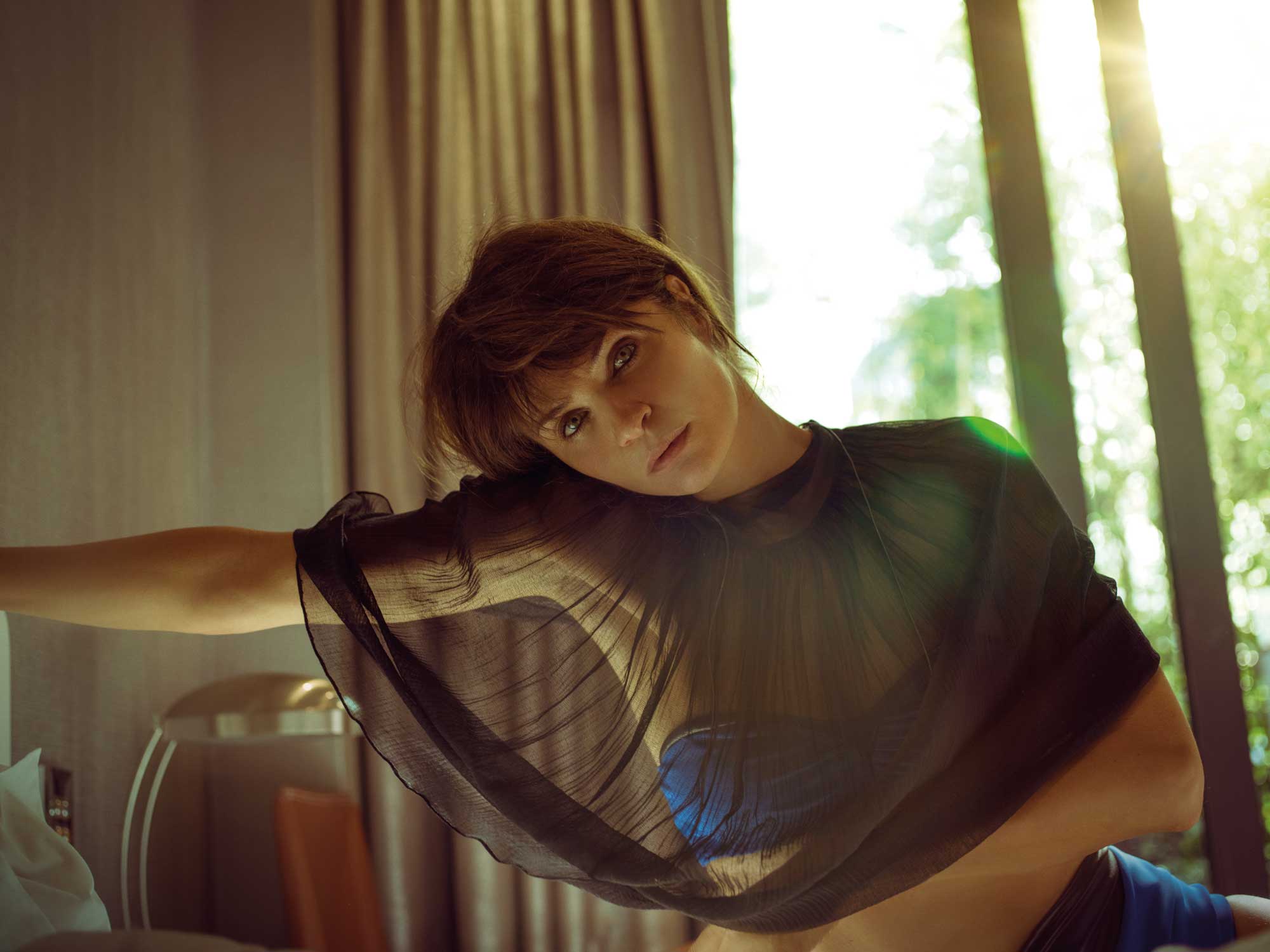

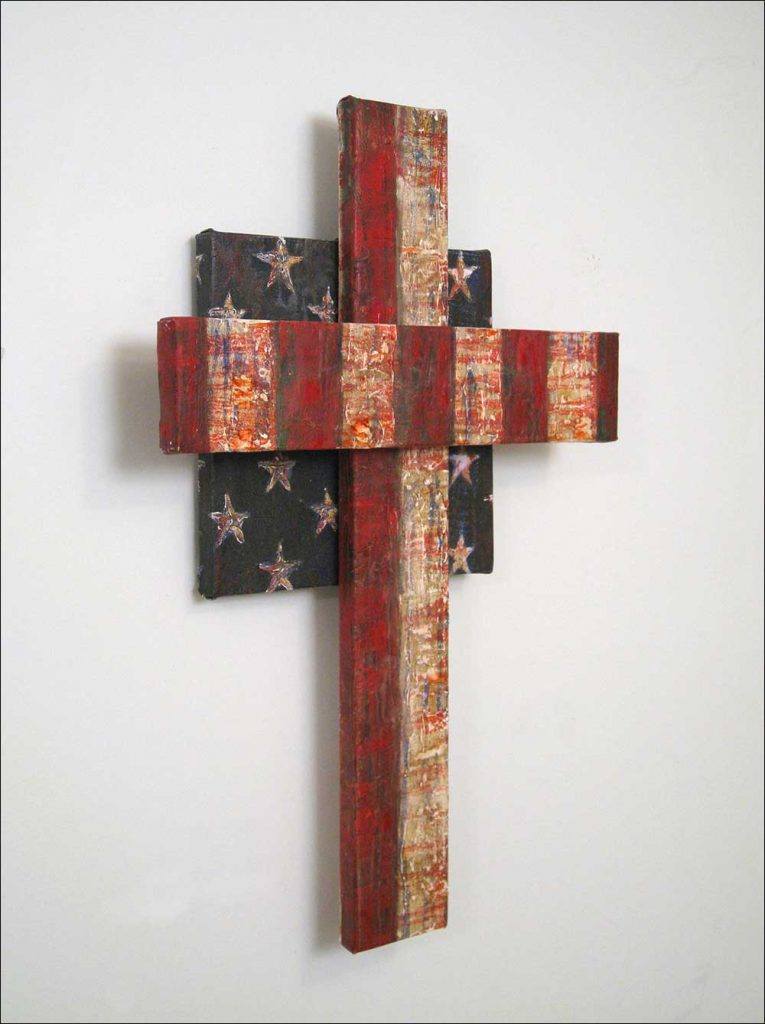

Cross Flag. 2012, oil on canvas, 33 x 22 in. Collection of Mike Dean and Louise Donegan.

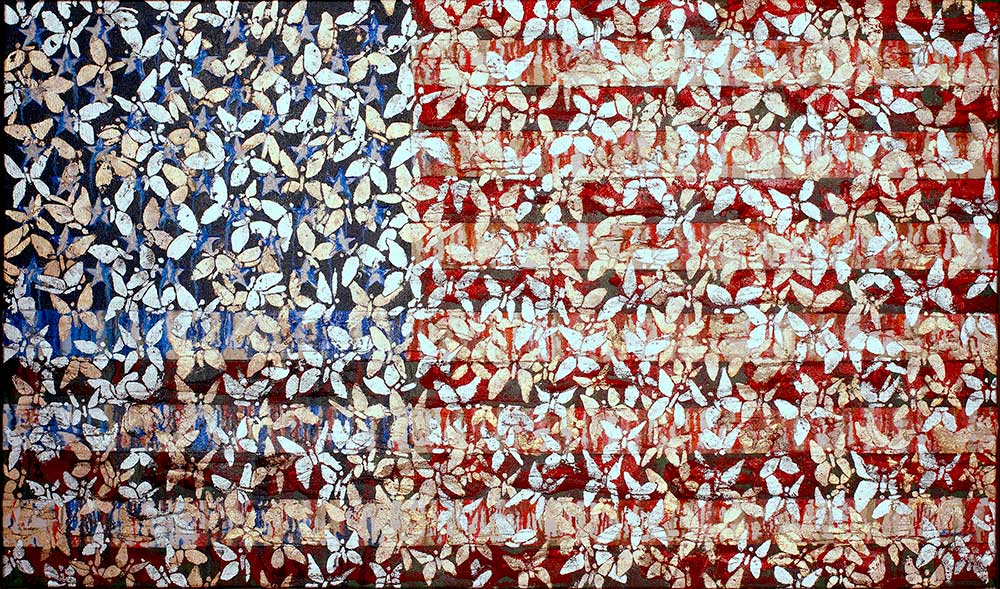

“When I was eighteen or nineteen I painted my first American flag,” he said. From the realism of a human face to the abstraction of a flag might strike you as radical. Not Grayson. “I can go from classical to complete abstraction in the same moment,” he said. “To me, it’s all tied together. I don’t see it as separate. Classicism is a million small abstractions. Little pieces of nothing. Everything is a pattern, pattern of behavior, and structure. And I was obsessed with this portrait thing. So I wanted to do a portrait of America. And I used all the classical techniques to create it, even though it’s a completely contemporary painting that looks like it is bleeding and people are moved by it. They are very moved because the red in the flag seems real. Why it looks like it’s bleeding is because of the grey-green Verdacio underpainting. When you see red or flesh over grey-green you feel as if it’s living. You can’t help it, the human eye subconsciously recognizes blood as grey-green when in the veins, before it oxides to red. I put the human in the abstraction.”

I had to mention Jasper Johns. No single artist owns the nude, say, or the bowl of flowers but Johns’ 1954 painting of the American flag is perhaps his most universally known image. For Grayson, this is a non-issue. “When I did my first flag it wasn’t about the art culture,” he said. “It was very personal. It was like doing a self-portrait. It was a portrait of the American flag as a larger character that you could relate to on a personal level. So I did variations of the American flag every time I wanted to do a portrait of America. Whatever was going on in the world, whatever moved me or I was affected by, I did a different version. It was a series of self-portraits.” He added, “That’s why I love Rembrandt.”

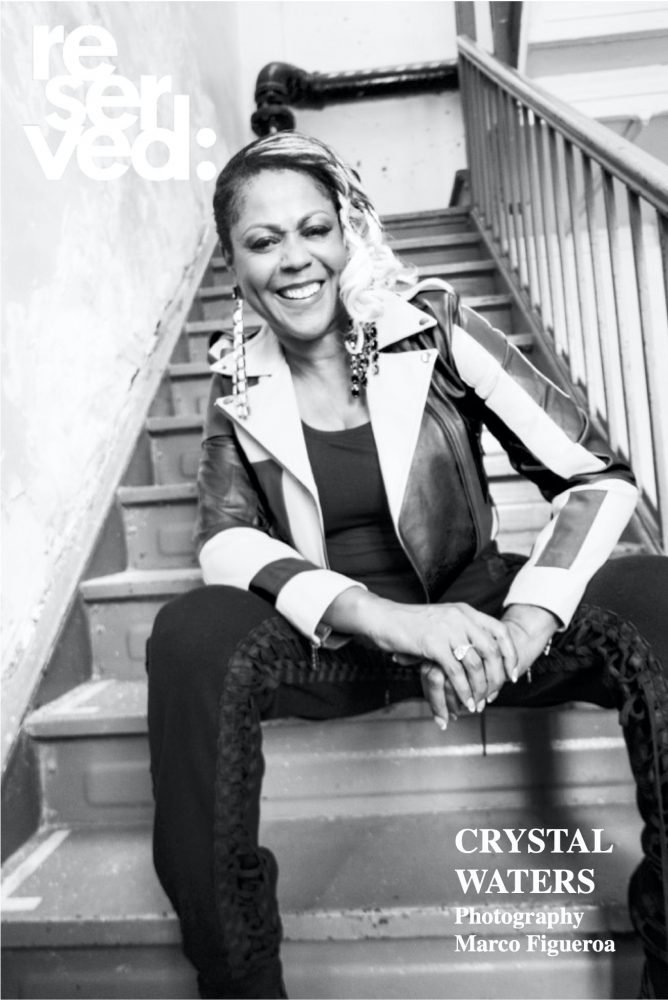

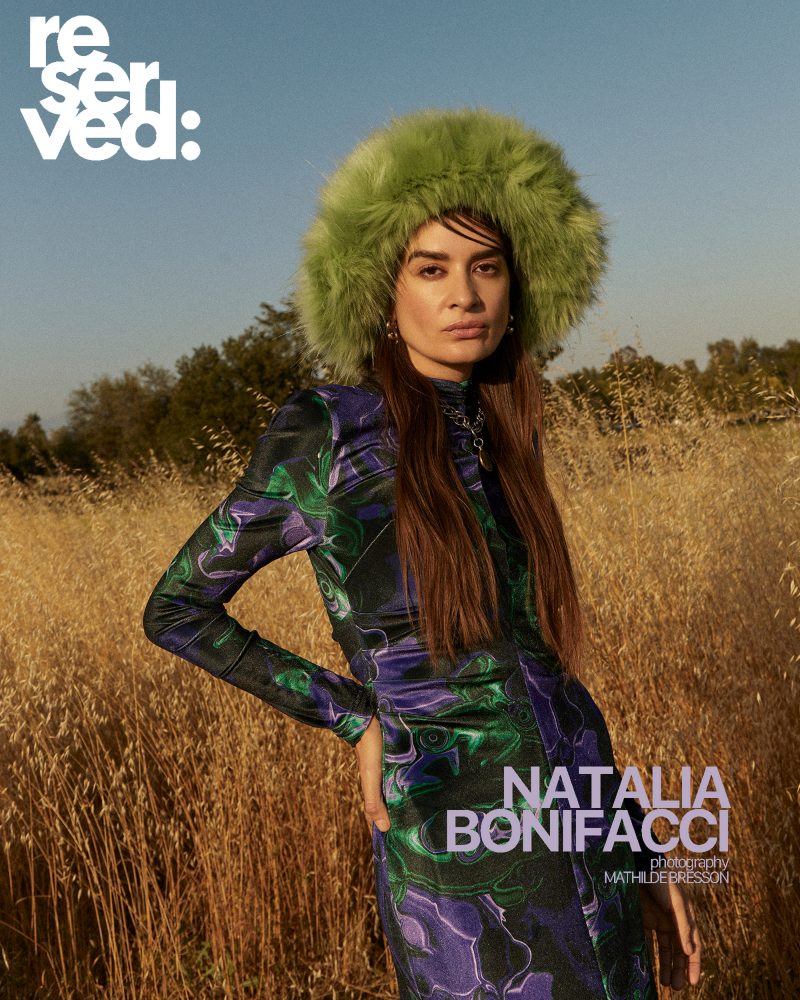

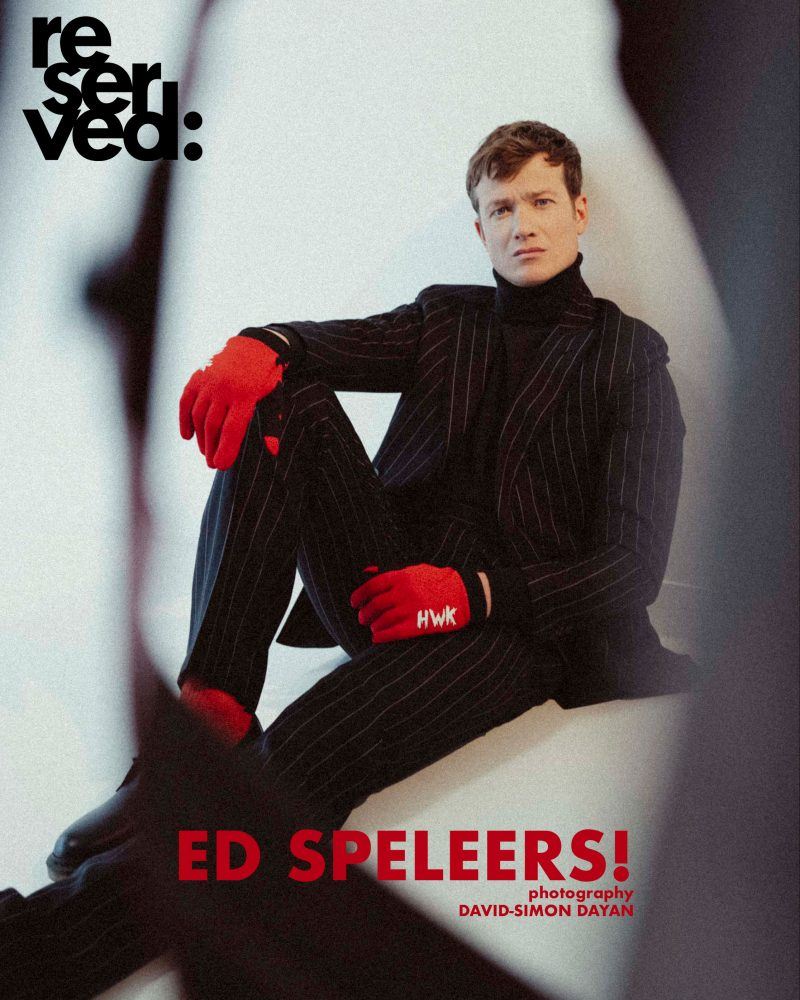

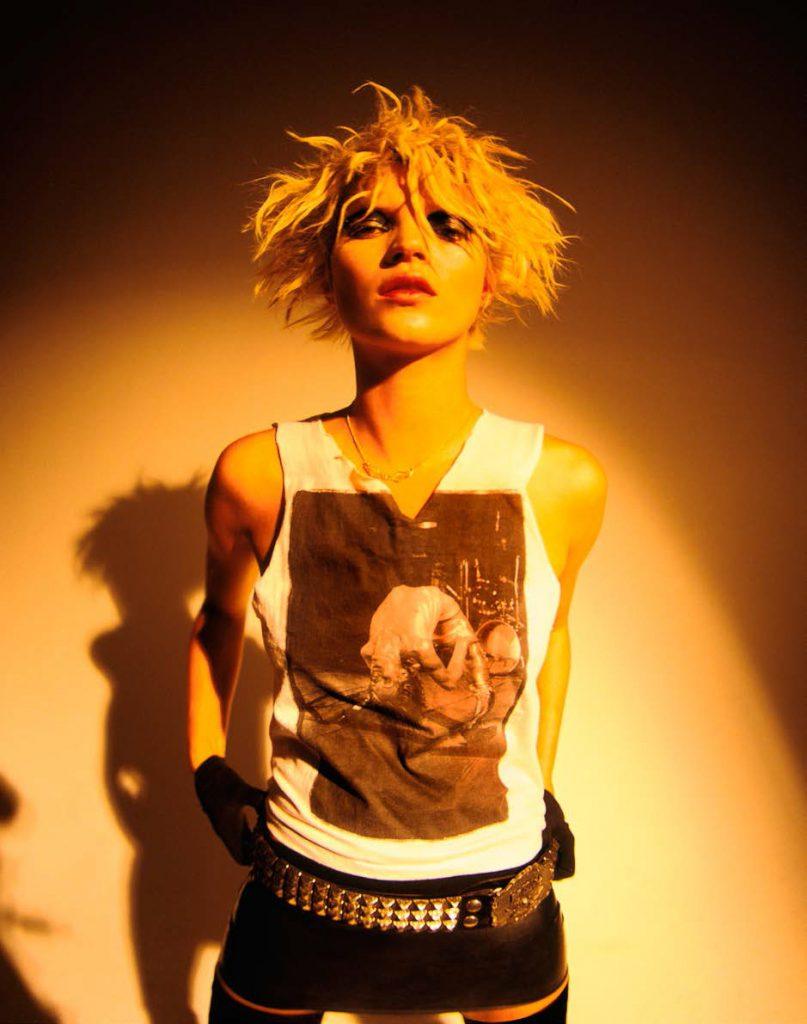

American Flag. 2013, oil on canvas, 60 x 85 in. Collection of Channing Tatum and Reid Carolin.

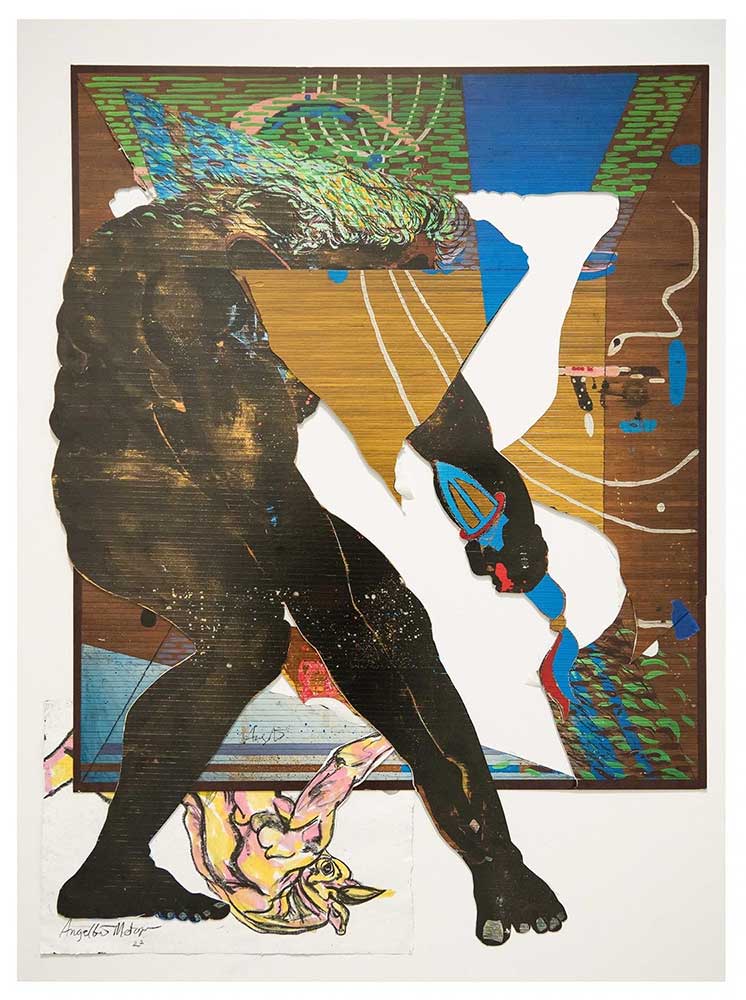

Then came another leap in Grayson’s art-making, again in a wholly different direction. During a trip to St Petersburg, Russia, he was taken to the house of Vladimir Nabokov. The late novelist had also been passionate about butterflies, and it was there that Grayson was told the saga of the European peppered moths which is at the core of his new body of work; Industrial Melanism. These moths, which can be black or white, were widespread across Europe before the Industrial Revolution. But soot from the burning of coal caused blackening everywhere and studies soon showed that black peppered moths were outnumbering the white, and 98% of the moths were black by the 1890s. Hence Industrial Melanism; Melanism being a word that means a darkening of the skin. “Everyone who followed Darwinian theory used this as an example,” Grayson said. “They thought that the white peppered moth species morphed gradually into the black species to survive.”

Grayson had learned about Neutral Evolution which proved that black moths had always existed. Natural Selection did not create them. Birds simply ate the white moths as they could see them on the black surfaces. “What Neutral Evolutionists believe is more often new species are instantly and spontaneously created, nature experimenting, genetic screw-ups, mistakes, accidents. And every once in a while you have a mutation, either a hybrid ‘monster’ or an instant internal reorganization of thousands of different things with thousands of factors. And one just happens to have the right traits to survive in that particular environment! It gives meaning to the outlier. And you ask why is that interesting or important to us? Well, Darwin believed that an ape-like primate evolved incrementally over many years into an early human. Which evolved incrementally over many years into a modern human. The one thing Darwin did not know about was DNA. And genetics to the extent that we know today. Other primates have 48 chromosomes. Humans have 46.” So if Darwinism was correct “you would have all the in-betweens up to a man, which we do not have. Evolution probably occurs in big leaps.”

American Flag. 1989, Oil on canvas 48 x 72 in. Collection of David J. Sussman.

And the moths? The Neutral Evolutionists claimed that the white moths hadn’t morphed into black ones. Upon the blackened walls they had simply become fast food for birds, leaving the black ones. A similar thing must have happened to Neanderthals and our ancestors.

Grayson buttresses his Industrial Melanism with the Hopeful Monster Theory, which is illustrated by a boy who was born very dysfunctional in every regard except one, which was that he could learn multiple languages in seven days. “Imagine if he was born a hundred years into the future?” Grayson said. “Imagine how that child would flourish in a world of artificial intelligence, robotics, computers. Because language processing might be the key skill to survival. Not getting food or cutting a piece of wood or doing the thousand mundane things that we do. So that child might be the next evolution of humans, and we might be the next Neanderthal in the lineage. I love this concept. This is the core of what drives me in art. Nature is almost like Dali’s frame waiting for a leap of imagination that can create the impossible thing.”

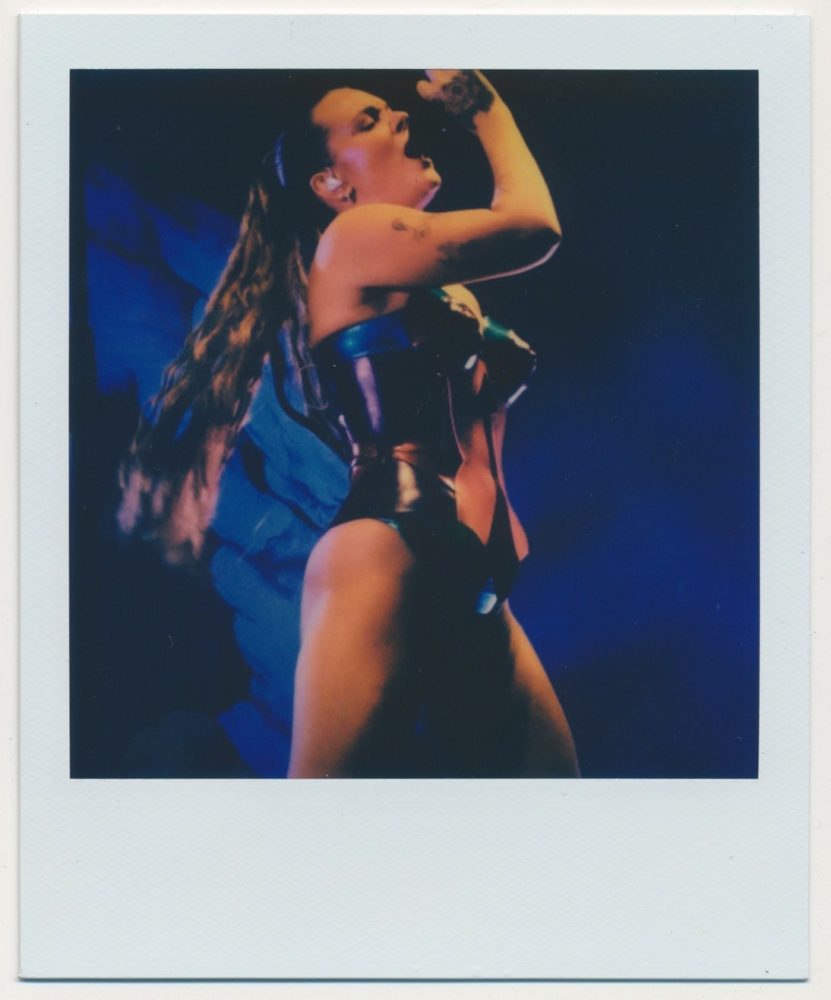

American Flag. (Industrial Melanism) 2016, White gold, Silver, oil on canvas, 24 x 38 in. Collection of Mr. & Mrs. Michael Zapata.

Industrial Melanism and Hopeful Monster Theory unknowingly powered Grayson’s work for twenty-five years, and he explicitly tied the concept to the canvas over the last several years.

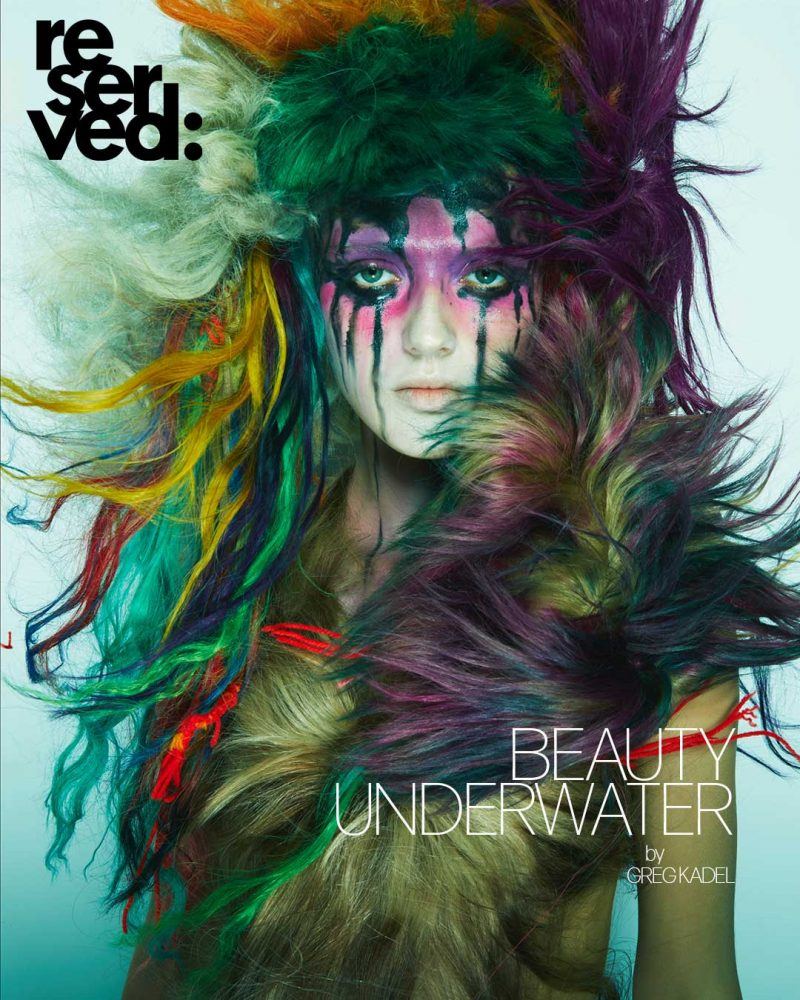

As his work was primarily rooted in darkness and angst, four or five years ago he decided it was high time to lighten up. “How I got into the butterflies was by pure accident,” he said. “Something I never expected. I hate butterflies. Five years ago I’m sitting outside in Connecticut working on a charcoal drawing. Dark, angsty, very miserable. I hate this, I am so tired of being good with power derived from darkness and always looking for that tiny little glow of light … the singularity that I had found in the Rembrandt portrait.

American Flag. (Industrial Melanism) 2018, Platinum, Palladium, 24k + White gold, silver, oil on canvas, 17 x 23 in. Collection of Mr. & Mrs. Michael Murphy.

“I want to do something that I would never, ever do … something pretty, appealing, happy. I thought what would I never do? I would never do a goddam butterfly! So I said to myself I’m going to paint a butterfly! But I can’t do a blue or pink or yellow butterfly, I’m going to do one in metal. That’s at least a little bit cool. I figured out how to take silver and press it into the paper. I’m not thinking about Industrial Melanism that I’d learned about in Russia. I’m not thinking about any of that. I’m figuring out how to become a different person, become a different human, enjoying things that regular people enjoy. But I can’t do a decorative butterfly, I’m going to use metal. Three or four years ago I started this with the butterfly idea … and when I did the first one I was not thinking European peppered moths. Because I just wanted change.

“But then I tied the ideas together. And then I started experimenting with all of the different metals. I spent a lot of time figuring out a way of using metal so that it doesn’t look like metallic paint. Every metal has a color quality that is created as it oxidizes. All metals start out a silver color, very white. And over a three- to six-month period every metal turns a different color. So when I did pieces I’m working with white metals. But I know which one is going to oxidize to which level …

“Just as I had used chemistry to make the red in the flag come alive, I became obsessed with mastering this technique of metal as a pigment. But not in a way that has been done before.”

But metals can change color, no? Silver tarnishes.

American Flag. (Industrial Melanism) 2016, White gold, Silver, oil on canvas, 24 x 38 in. Collection of Mr. & Mrs. Michael Zapata.

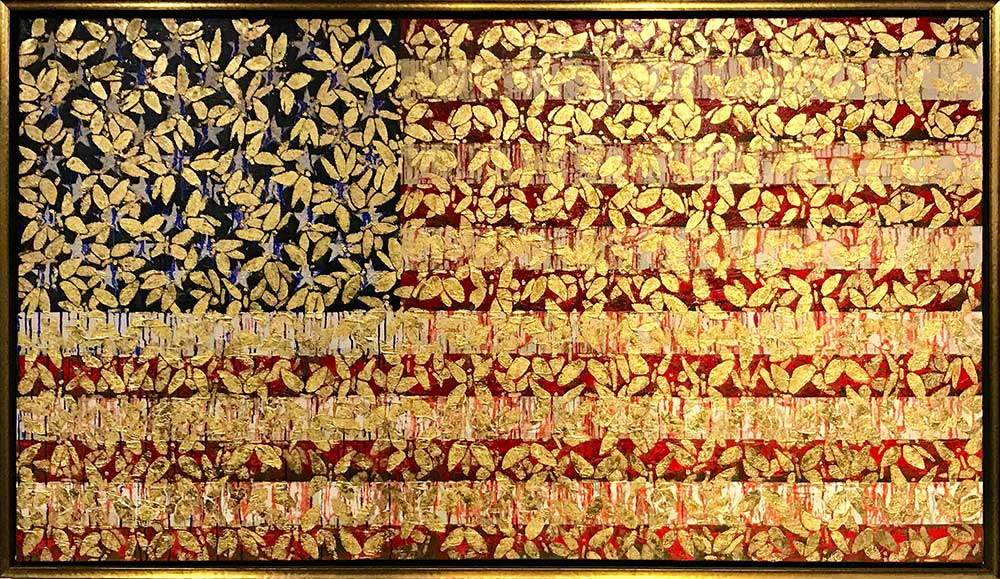

“That’s why I use platinum and palladium which are more rare. The reason why white gold turns rusty color or pale yellow is that it is made with silver. So depending on the percentage of silver in that white gold it will turn that color or not. Palladium has very unusual reflective quality. Platinum has a slightly brighter reflective quality which is almost like silver. I have used everything in every variation. Variations can be interpreted differently. I love palladium and platinum. They’re my two favorites and white gold. They only seem to change color depending on the viewer’s perspective as you move. I did create a 24-carat gold American flag in 2017, which everyone interprets differently. Chemistry is behind the Neutral Evolution of form and perspective changes what it means.”

A last question. What made Neil Grayson so interested in evolution? Bright question, chiaroscuro’d answer.

“Much of my family had neurological or genetic illnesses or deteriorations,”

Grayson said. “Europeans have Neanderthal genes which are associated with depression and addiction. And maybe artistic obsession? They were the first painters.” He instanced several, including a grandmother with schizophrenia, his father’s dementia with an Alzheimers-like deterioration, and an older brother with Down syndrome and an extra chromosome. On my father’s side, I would say more than half the family at one point or another was hospitalized.”

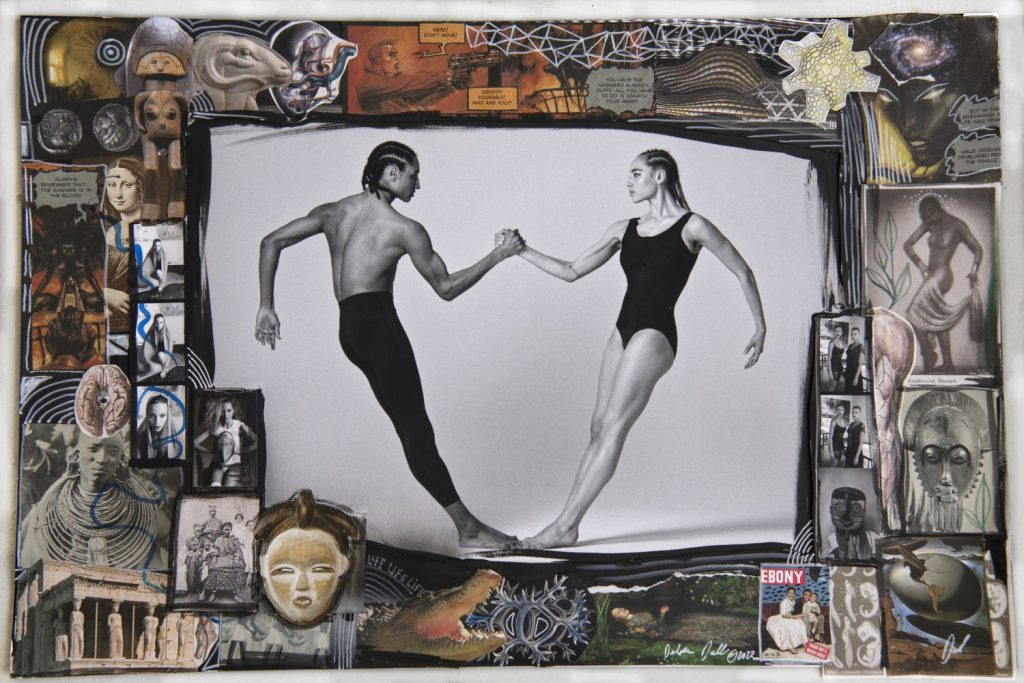

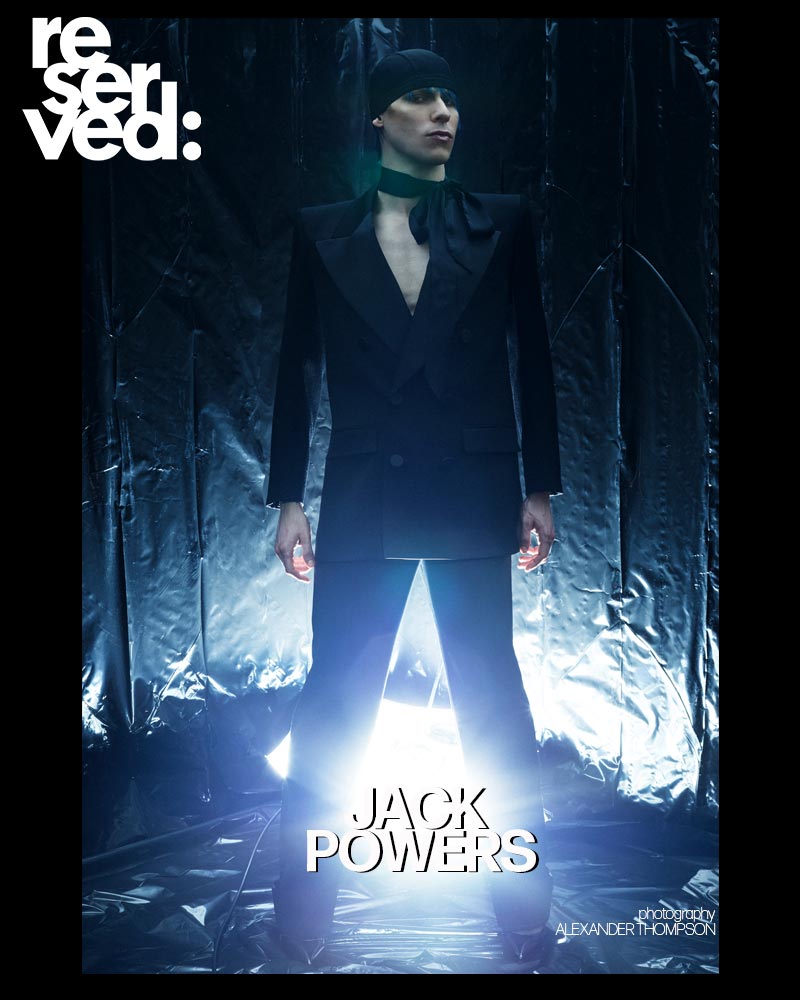

Portrait of America (Industrial Melanism). 2017, 24K gold, oil on canvas, 44 x 78 in. Courtesy of Eykyn Maclean Gallery.

Does this not fill him with some level of dread?

“It used to stress me out all the time,” he said. “On the other hand, I’ve come to the understanding that it may be a blessing. That happened about two years ago. I know that’s a strange way of looking at it, but if I didn’t have all these things surrounding me, I never would have had the interest and the motivation and the desire to investigate and make meaning of it. And I wouldn’t have the content and the fuel and the core of the ideas for my art. So it’s a double-edged sword. In one way, yes, it concerns me. I’m scared. But then at a certain point, I said to myself I think I’m incredibly lucky.”

American Flag. (Industrial Melanism) , 2017, White gold, Silver, oil on canvas, 39 x 66 in. Collection of Patrick Ryan.